David Shifrin

The interview with David Shiffrin, orchestral soloist, recitalist and chamber musician and professor at The Yale School of Music, took place on June 10th 2019 at Yale and was edited by Heinrich Mätzener.

Introduction

HM: The purpose of this project is to show different ways of being successful with clarinet playing. I started the project by having interviews with Swiss clarinetists around Zurich, where I live and work. Then I met German and Austrian clarinet players, as well as colleagues of the French speaking part of Switzerland and colleagues in France.

DS: You’re in the center. Every direction, you have all those schools.

HM: It was amazing: everybody was so cooperative; well-known names like Michel Arrignon, Alain Billard, Pascal Moragues… It is really beautiful work and an exciting project, and today I feel very happy to meet you. I met also your former student Ramon Wodkowsky. He often comes to Switzerland. Recently I tried his mouthpiece “Philadelphia.” I like to play it on my Buffet clarinet.

The tradition of the old French School in the USA

HM: I also talked to him about this project. He knew quite a lot about the tradition of the old French School, brought from Daniel Bonade[1]to the States, continued by David Weber[1], John Mohler[1], Donald Montanaro[1], and a lot of other famous names.

DS: And students like Robert Marcellus[1], Stanley Drucker[1]. Most of the best known Americans. I think some studied with Ralp McLane[1] also: Mitchel Lurie[1], Dominique Fera[1] in Los Angeles and the film studios, throughout this country.

HM: And I think Ralph McLane studied with Gaston Hamelin[1], Old French School.

DS: I think you are right, I’m not really sure. (Shows a photo, with Ralph McLane], William Kincaid, Marcel Tabuteau, and Eugene Ormandy as a young man). I have this picture from Hans Moenning. He was a repair man in Philadelphia. He worked on everyone’s’ clarinet. He died in the 80s. When I was a student in the 1960s, you would go into his shop and see Benny Goodman[1], Robert Marcellus. He had some pictures; he gave me that one of the historical Philadelphia.

HM: Great!

David Shifrin’s professors

HM: Who were your professors?

DS: Actually, my earliest teacher was a public school music teacher who gave me a great foundation. And he sent me to another Bonade student, when I was about 13 years old, named James Callas. He studied with Bonade I think at Curtis and played in the NBC with Toscanini. He was retired and teaching kids in New York when I was a kid. I studied with him for a little while, and also Robert Bleiman from the Metropolitan Opera, David Glaser from the New York Woodwind Quintet when I was living in New York as a kid. Then I went to Interlochen.

It’s a boarding school for music, and I studied with Fred Ormand[1], who is still around, still teaching privately.

HM: Fred Ormand is still teaching?!

DS: He was at Michigan for a while after me, then I went to Curtis Institute for 4 years, studying with Anthony Gigliotti[1], and in the summertime I went one year to the musical Academy of the West to work with Mitchel Lurie[1] also a Bonade student.

And another summer, summer school with the Cleveland Orchestra and I studied with Robert Marcellus[1]. So, those pretty much all my teachers. A lot of very fine teachers! A few different schools but primarily Bonade.

Development of sound concepts

HM: What would you say was the most important idea about sound that you learnt in the time of your study time? Has it changed?

DS: Of course!

HM: Today, the fashion is a bit different of what we learnt.

DS: Well, of course, since I studied with so many students of the same teacher, to me it was fascinating and somehow confusing that they all played so differently. They all studied with the same teacher, but they didn’t sound the same. And in addition, in my generation and going forward, we had more and more access to recordings. So you had influences, especially in the United States, because there were German influences and French and Jazz, so you heard so many different things. And then with the recordings available all the time, you hear so many different schools. And everybody else hears everybody else and I think it became in some ways more homogeneous, not so much vibrato in England, in Czechoslovakia only, and everywhere else no. And then in England when I was a student, Gervase de Payer, Jack Brymer, Jack McCaw, they played with a very wide vibrato! And now clarinetists in England very little.

HM: Yes.

DS: And I listened to all the recordings from France too, like Lancelot and Delécluse and they played with a very fast vibrato.

HM: Yes! There is a story, about Bonade coming back to Paris and listening to Ulysse Delécluse. He played with a very fast vibrato. Bonade must be astonished: this was not what he learnt with Prosper Mimart. I don’t know why there was this break. I also asked French clarinetists.

DS: Different approaches with equipment, like mouthpieces. But it was amazing to me that also the divide with the German system and the French system, yet I found more differences between different players all playing the French system and different players all playing the German system with each other. Then sometimes some of my favorite players on both. For instance, I thought the tone quality from Karl Leister could often be very similar to Robert Marcellus and playing completely different instruments! But I was listening to Leister and any number of German clarinetists and there are vast differences: Deinzer and so many other clarinetists didn’t sound like the same instruments the way Marcellus and Leister would sound. So all these different schools, but as I said earlier everybody is much more mobile, travelling everywhere, going to competitions, listening to recordings.

HM: Yes!

Today’s concept: creating the sound by the equipment

DS: And that is a much more universal ideal and sound that I hear. When I do auditions in Yale, here, every year, because it is a graduate school, people come from all over. They come from Europe, from Asia, and from everywhere in the United States. So you hear players who have vastly different backgrounds, but there is much more uniformity in how they produce a tone, and I think everyone is for the equipment to make that sound.

HM: Do you think it’s darker than twenty, thirty years ago?

DS: I think so, and you listen also in recordings. It is in some ways a more vibrant and brighter sound. Even Bonade in the recordings that we hear! And then it became more mellow and darker and then, you know, I’m still looking for the best combination of all of them! Personally, my ideal… I think there was one day, 17 years ago, where I achieved it for one minute. Always looking for that!

HM: That’s artists’ life.

DS: I wanted to be mellow and warm but still be vibrant and expressive.

Don’t sacrifice the flexibility for a dark sound

HM: What would you say artistically, what do we have to achieve with a sound quality? How important is it to play with a dark sound?

DS: I think it is lovely to have a dark mellow sound, but the risk is that you don’t want to sacrifice flexibility, beauty of legato, beauty of phrase and making different colors, and articulation and playing in tune. I’ve seen so many students who just play on harder reeds. They think, “Ok, now I have a big dark sound.” But this is one sound inflexible. So try for all of these things. I think the tone quality has to be beautiful, but it doesn’t help if you can’t articulate, if you don’t have the flexibility, if you can’t play in tune with yourself! So we look for all these things, and I think that’s what everyone is looking for, and what every instrument should be able to do.

Embouchure

Double lip embouchure as a basic for sound production

HM: It goes always together, equipment, like reeds—you spoke about hard reeds—mouthpieces, it goes always together with embouchure forming, voicing, and tongue work. My opinion is that one of the advantages of the Old French School technique was the playing with double lip embouchure: it was not possible to play with hard reeds…

DS: No, my first major teacher, James Callas, who had studied with Bonade, taught me to play double lip, and to play very soft reeds. He always talked about legato and colors. I think I learned a lot from that. But when I started to play more with other people in ensembles and in orchestras, it didn’t work for me anymore; I couldn’t make enough sound.

HM: Oh, it wasn’t loud enough? Maybe this was the reason why they changed also in France?

DS: Maybe, but also, I found out that if I tried to play loud, maybe I could play louder, but the tone became so different; it became very strident and I didn’t like it.

HM: But I think the advantage of double lip playing is not only the flexibility in the legato; it changes the shape of the oral cavity in a positive way.

DS: Oh, it absolutely changes the voicing! And so what I learnt from that is that you can voice as if you had double lip embouchure without biting the upper lip, by using all the muscles that are engaged when you block your upper lip over, you feel immediately, the air stream is arched, the soft palate goes up. So if you use the muscles without biting yourself, you have the best of all.

HM: Do you want your students to try some tone exercise with long notes, playing with double embouchure?

DS: Sure! Just to feel—to engage—those muscles and tell them: “ok now you can do it without the pain!”

Playing double lip replaces complicated descriptions of embouchure

HM: I think it’s a good way. It is very difficult to describe the voicing that is happening inside the mouth, and when they play double lip, they can learn it by doing.

DS: Yes, instantly. “Can you feel that? Ok.” You know some of my teachers would describe thinking of the mask from your eyes all the way to your upper lip, of bringing it down, and you feel the same kind of thing. And also to shape the vowel position, so that the air is arched: in French like the “I” “OU” sound; in German the “U” when you raise—same thing that happens when you drape your lip over your teeth.

HM: Do you pull down a bite the whole mask, not only the corners of the mouth?

DS: Oh, everything from the eyes to the upper lip!

Keep the bottom lip flat

HM: Do you think it is important to tense the bottom lip or to make a cushion with a relaxed lip?

DS: I try to keep it flat. I was always taught that my chin has to be flat and in order to do that I learnt to put the lip on the lower teeth. Yes exactly.

HM: And the pressure, we always have to say, “Don’t bite.” But there must be a certain pressure to make the reed vibrate. I read in Bonade’s book, he opened the mouth and when the angle comes near to the body, he builds up a certain pressure against the reed. But also, do you use pushing the clarinet a little bit against the embouchure?

DS: Sure, yes, I bring it to me.

Find the right embouchure line on the reed

HM: To stabilize it without biting, keeping the jaw open.

DS. Yes, I bring it to me instead of crashing (?) down. And it’s the angle, oblique rather than straight in, that gives the right pressure on the reed and does not close the reed. I think enormously important is, where you’re in contact with the reed. Just as a starting point, I was showing the students to look at the mouthpiece sideways to the light and see when they begin to see the light [between the mouthpiece and the reed]. That’s where the facing really is [beginning]. Don’t put your lip higher than that because it would be different every time, but if you use the position where the facing starts, it gives much better consistency. And [there are] different mouthpieces, you know, so many different curves, so many different links, you have to find what works for you and what works for your equipment.

HM. And it depends from your physiognomy, from your tooth position.

DS: And that goes for the angle as well.

Voicing

HM: Difficulty for me is to get the students to have the independence between embouchure forming and shaping the oral cavity, to get a flexibility for the different registers. I think we should change the tongue position playing high notes or playing in the chalumeau, one could say, this is the art of voicing.

DS: Yes, and it is very hard to teach because what happens is that people overcompensate, they do too much.

HM: I’m sure you know “The Art of Clarinet Playing” by Keith Stein [2] </ref> [1].

DS: Yes. He thought about that fifty years ago!

HM: He’s writing very detailed about every aspect of technique. There is really a danger to get too much information, and to get confused and stiff. After describing accurately all details about the technique, Keith Stein adds a very good chapter about relaxing. He is right to go first of all step by step with all different parameters: upper lip, lower lip, going from outside to inside, voicing, breathing etc.

Find a tongue position that works for all registers with the least amount of adjustment

HM: How do you teach? Would you describe the position and form of the tongue, the back of the tongue maybe holding more stable than the tip of the tongue, who is placed near the reed, but moving up or down, following the register being played, as part of the voicing?

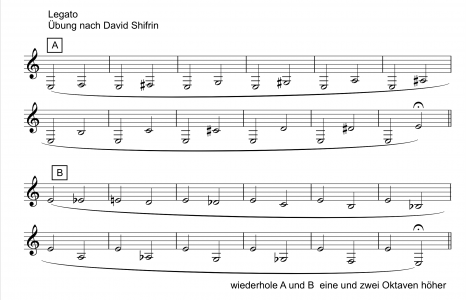

EXERCISES

Start from playing the 12th in tune

DS: I find it’s very important to find a position that works with the least amount of adjustment, where the jaws are open but the tongue is high and the air stream is arched and you could play the 12th as in-tune as possible without making any adjustment.

Legato between different Registers

DS: Start from there and one of my favorite warmups is just starting on the low E and slurring to an F, then a whole step to F#, then G, the minor 3rd, and try to do it with the least amount of adjustment on the interval and if it is not working, find the position where it does work. And then have that be your base line and then slight adjustment for voicing and do not over voice everything you play.

HM: And what about the back of the tongue, do you change its position, different for lower to high notes?

DS: Touching the upper teeth?

HM: Sometimes, maybe for the high notes, in contrast to the lower registers?

DS: A little bit. But again, it is dangerous to overcompensate and sometimes it’s coming intuitive, when I go for a high note, especially like the high F, with normal fingering, if you try make it too small you get the undertone; if you open up too much it spreads and splashes. But I have to open up sometimes more than you think, you know passages like we have in the piano, going up to the high F from a lower note, in Debussy Rhapsody, Poulenc Sonata from the B flat up to the F, Copland Concerto, also from B. If you close too much, you get the undertone. So, it’s a lot of kind of extra narrow, right?

Sarah Willis’ MRI

HM: Yes, there must not be too much too much tension, but some little changes are necessary.

DS: Yes, of course, do you know Sarah Willis, this young woman, excellent horn player, who did a video, where she plays the horn in an MRI machine YouTube and they videotaped what her tongue was actually doing when she played low notes and high notes? And it was exactly what you might think, almost what you would do if you were whistling low notes, where the tongue has to be way down and high notes up. What she did so that she could get into the tunnel of the MRI: she put the horn bell on a hose so she could play it on the MRI machine with the mouthpiece, and she must have had a synthetic mouthpiece because you cannot have metal—anything that would be magnetic—in an MRI machine. That’s on YouTube, if you just looked for horn, tongue position, MRI, it comes right up. I was astounded how much motion and sometimes how little motion she does with her tongue.

HM. I will look for it. Bruno Schneider participated in a research project [3] about breathing.

Use the vocal cords to influence the speed of air?

HM: As you said, there are very small differences in positions. There are people who try to involve the vocal cords, to make the air maybe a bit faster. I tried it but did not feel comfortable.

DS: I don’t know. The only time I try the vocal cords is to make a special sound like something jazzy, to growl.

HM: Yes, real singing into the instrument while playing.

DS: Yes, it’s very effective and sometimes (laughs) you have to be careful.

Articulation

HM: What would you say about articulating? We can use different points of the tongue touching different points the reed. Given by the musical context, we can to touch the tip of reed, or just a bit lower. What's your most common method?

The tongue is the damper, the hammer ist your wind!

DS: I try to articulate right at the tip of the reed, always, without exception. Which part of the tongue varies so much with individuals I think, because our structure is different. But I think it is very important when I teach articulation, I always play inside the piano and I ask “what would be the comparison, analogy inside the piano to the tongue? And most students say the hammer. I say: “No! The damper! And the hammer is your wind!” Releasing the damper allows the string to vibrate. And once that concept sinks in, sometimes it’s a really, really dramatic improvement in articulation, because the tongue doesn’t make a sound, but it can stop a sound.

Keeping the tongue in the same consistent position

DS: And so, keeping it in the same consistent position allows you most efficient articulation but also the consistency in the tone production. So I try to keep it in the same place as much as possible.

HM: And also when you don’t need it for your articulation, it stays very close to the reed?

DS: It’s ready! And I like the analogy with the string player too. You know string players are not going to go [with a huge movement to strike the string] (laughs). They keep the bow where it needs to be.

HM: I think it’s one of the principles that Bonade also taught, to stay with the tongue very close to the reed.

DS: Have you seen the Clarinetist’s Compendium? Do you know that book? [4]. There’s a whole chapter where you start with the tongue on the reed, and you blow, and withdraw it slowly, until you get a tone.

„Staccato is an interruption of the tone by touching the tip of the tongue to the reed and and not by a hitting motion.“

DS: That’s it, don’t go any further (laughs).

HM: I even know, I’m not sure, you know that Vade-Mecum by Paul Jeanjean <rew>Jeanjean, Paul. 1927. "Vade-Mecum" du clarinettiste six etudes speciales. Paris: Leduc.</ref>, there is an exercise with very quick staccato. He calls it tremolo, but I don’t know is that unlike a vibrating of the tongue, touching and not touching, almost the same position, I don’t know really what he means, I think it is a reflex-like vibration of the tongue moving back and forwards, in very small movements, to the reed.

DS: Is that a flutter tongue?

HM: The French clarinetist, Sylvie Hue, told me when wind bands have to play transcriptions for strings, they try to imitate the string tremolo in this way.

DS: Yes, because the flutter tongue sounds ridiculous.

HM: Flutter tongue would be different. Hans-Juerg Leutholt, my teacher in Zurich, who himself was a student of Louis Cahuzac, told me that: to stay with the tongue on the reed, very softly and almost without pressure, and then blow until the reed starts to vibrate and then let the tongue make these fast, reflex-like movements on the reed. It depends how much surface of the reed is touched by the tongue. When there is only a very light contact on the tip of the reed, it can continue to vibrate. I think this would correspond to your principle that the tongue should always be in a consistent position, very close to the reed

And the French clarinetist Pascal Moragues told me that he uses to create a very soft ending of the note playing staccato, that he lets ring the reed and does not really stop the vibration suddenly, he just damps it a bit then lets vibrate it again, releasing with the tongue. I tried it. I didn’t use it before, it’s a nice effect.

DS: I tried it sometimes, but it tickles.

HM: I think it should not tickle, if I touch the reed only with a very small point at the tip of my tongue.

Anchor tonguing

HM: Did you ever try other methods of tonguing, like anchor-tonguing?

RS: No but some great players do. And I think I can only guess because I haven’t seen x-rays or MRI’s of every player, but I know Mitchell Lurie for instance, who was a great player, he told me he anchored, kept the tongue at his bottom teeth. But I think you compensate for it in different ways. Your tongue raises and you find a way to arch it. My daughter plays the clarinet and that’s how she tongues, and I tried to change her, but she is comfortable, and it’s not going.

HM: I think this is not necessary to change if it works.

DS: If it works, exactly. And you know that’s another thing I try to remember in teaching—sometimes it’s hard—that somebody is doing something that works beautifully but it’s not the way you do it, you have to say: keep it like that. But if it doesn’t work and they are resistant to what you’re saying, that makes the point that “If it sounded great, I wouldn’t say a word” (laughs) so let’s see what we can do to help!

HM: It’s difficult when somebody repeated certain things during years to change it.

Breathing

HM: Let me go more inside the body and come to the breathing. How do you explain the breathing we use for playing a wind instrument, to sustain with our air a sound, in contrast to the breathing in everyday life? Of course, if it works, you don’t say anything.

Use your full capacity

DS: No, I do, I always say something, because I think most players don’t use their full capacity. I had students, wonderful athletes in fantastic shape, the height of their physical ability, who couldn’t hold a note half as long as I can, and I’m an old man. It’s a technique, using your full capacity, and I think part of wind control is the embouchure too. I’m sure we’ve all noticed that oboists can usually hold a note longer than a tuba, you know if the opening is really small, you could go on for a long time.

Don't waste a lot of air

With clarinet if you’re achieving a tone efficiently, not wasting a lot of air, you can control the volume and the sound much better than if you’re just blowing your wind all at once. And I find that the whole idea of arching the airstream and keeping it small really helps with the wind and the concept of having almost an opposite effect of being as open as you can with the jaws so, you’re using the whole facing of the mouthpiece and the reed is vibrating with keeping the air stream really small. So you have a small fast airstream making the reed vibrate and wide amplitude. That takes a while for some students to get the hang of it, but you can really hear when they get it.

And the tone quality becomes more consistent and so does the pitch because it brings the lower register up and some of the high register down, so the 12th become better in tune. (see also Intonation)

HM: It’s a very good description, opening the jaw, focusing in a mask maybe for lips and the tongue position and using not a lot of air, I mean, when the air is so focused, you don’t have to blow as much as you can.

Control the speed of the air

DS: True, my overly simplistic nonscientific explanation for students, just to get the concept, is to think of the vying control. [If it is] loud, [in contrast to] soft, [observe], is the amount of air you get through the instrument. The quality of sound and the vibrancy is [linked] to the speed of the air, [not to its quantity].

So, to play a really vibrating loud sound that’s not distorted you have to get a lot of air through a small opening and to get a really beautiful ringing pianissimo, you still have to move that air, but less of it. You have to move that sound connected with the air. And I find that that explanation, whether that’s happening physically or not, scientifically seems really to hold true.

HM: I think that a physician called Bernoulli who taught about the velocity of air or water in thin or wide tubes. The same amount of air moves very fast through thin tubes and slow in tubes with wider bore – creating the same pressure.

DS: Of course. I have heard teachers that helped me understand with just taking a garden hose with the water coming out, you’re putting your finger on it so it has to go through air, and hits across the road. So, do that with your wind, it’s the same thing.

Breathing in

HM: What is the difference in the oral cavity while inhaling and exhaling?

DS: I think that the throat position for breathing in is totally different than for playing a sound. And the “O” vowel sound creates an optimal opening (makes a whiff) for a dramatic physical intake, the best as possible to enable inhalation.

Finding your diaphragmatic support

EXERCISE

Incremental breathing, compressing the air

DS: The other thing that I have my students to do as an exercise is incremental breathing, where you breathe as many as ten times, intake, without blowing. Then I get the ''radio voice'' (laughs). It automatically engages whatever the diaphragmatic support is, when you have that much air, that deep. Because other times you do about five, you feel like you can’t do anymore and physically, you react because you know you have to, by compressing that air, making room for more (demonstrates). And you can certainly even hear it in a speaking voice and I can imagine that announcers on radio or television use a similar technique, and so do singers (imitates a speaker with a very resonant voice).

And it works on the instrument as well. And it teaches the students what their true capacity is, because nobody has time in the middle of two phrases in Mozart clarinet concerto to wait (makes the movement), but that exercise can teach what the capacity is and keeping the throat as open as possible to try to always use the maximum intake of air.

HM: And would you say, you stay active while blowing with the intake-breathing muscles, but not with the intake position of the throat?

DS: No, not the throat, but that’s the intake valve, just like you’re pouring when you’re taking it in. You don’t want to go through a funnel and take a long time to get it, you want to be as big as tube as possible and use your breathing muscles to do that and then immediately go to the tone production mode.

Practice the transition between inhalation and exhalation

EXERCISE Rapid inhalation

DS: And that’s a very important exercise too: finishing a phrase, keeping the air moving quickly, and then switching to the intake vowel and then going back to the inhale phase. It could be done very artfully and quickly, but it’s something that player has to be aware of and practice.

HM: That’s like what singers do. After a phrase they have to relax very quickly, to let fall in as much air as possible. Starting the new phrase, they stay a bit in the inhale position of the chest and diaphragm and back. But we have to change the throat, and the tongue positions beginning a new tone production.

DS: Right.

HM: It’s a very good exercise, thank you very much!

Fingertechnique

Handposition

HM: I think, for finger and hand position, one of the difficulties is to find the right position of the thumb rest and the right form of the thumb. What you would say where is a good position for the thumb rest?

DS: It’s different for everyone because we have different shaped hands, and that’s why I like that a lot of the instruments now have one that slides up and down. And sometimes I found it difficult with some technical passages I never had before. I looked and saw that the thumb rest was in a different place! And so the hands were not exactly where I expect them to be. And usually, on my instrument, I am most comfortable with the thumb rest as high as possible.

HM. Yes. I also have the thumb rest as high as possible.

DS: You know the students who have smaller hands might need to be down there to reach all the keys. My hands are not that big, but I have no problem reaching all the pinky keys and I feel like I can keep them in a most relaxed efficient position. In general, I like to practice difficult technical finger passages where I have to move the fingers the least enough. It stands to reason to be the most efficient with the least distance.

Legato - more than just the fingers

HM: Bonade writes about legato-finger technique: “Legato fingers” in [6]. Do you think it’s a good thing to use? Ken Shaw wrote about this technique on The Clarinet BBoard (2006-02-02 15:54):

"Bonade describes his legato fingering technique in "The Clarinetist's Compendium," which is, unfortunately, out of print. Larry Guy has done us all a tremendous service by putting this material and much more in "A Bonade Workbook (2007)"[7].

DS: Bonade's idea was that you must move your fingers slowly to get a perfect legato. The feeling is "squeezing" your fingers down on the keys, so that the pitch changes smoothly, with no pop or click. Bernard Portnoy, a Bonade student, showed it to me and had me practice by raising each finger slightly and then floating it down on the hole.

Bonade used the first etude of the Rose 40 Etudes to teach legato fingering. It's incredibly difficult to get a smooth legato on the wide leaps, and I'm told that Bonade used this to show young hotshots that they really couldn't play very well (laughs).

I found it confusing because what works for me for the best legato involves so many things, not just the fingers. I mistook the thing that the fingers must be very gentle and very light. I think they should be very strong. Squeeze, not to strike the tone whole or the keys, but quite a bit of pressure, almost the way you think about the left hand of a cellist. You think the legato comes from the bow, but the left hand has to really be very strong. But in their case, they have to get the strings to the fingerboard in order to get a harmonic. What I find [very important]: the voicing of the wind, and the support, so that you are really playing between the notes and not reacting to the turbulence of the wind while changing notes but playing through it. And then being very definite with your fingers. For me that’s the way I practice legato.

HM: You would say, you do small movements with the fingers?

DS: Yes, I mean moderate.

HM: And with slightly bent fingers, a movement that is controlled from the first finger joint?

DS: Another thing that I was taught for the hand position is just imagine you’re holding a tennis ball. Then move the whole finger.

Learning difficult passages

HM: Do you have any suggestions how to learn difficult passages?

DS: (laughs) You know the standard conventional wisdom is that you start slow and you get faster. But I found it’s possible to learn things faster by taking them it in its components. Every instrumentalist does that from pianists to string players: to play things in different rhythms. I find that tremendously helpful, and in different combinations of slow and fast [note values], but always in the sequence that you want to learn. I think what you are doing to a certain extent, is that you are training your brain and your physical motions with your hands to have a conditioned reflex that you create. But the brain is not quick enough to just go through the whole sequence all at once, but [it works] doing the sequence in different patterns. I’ve done it with students and it’s pretty dramatic if there’s a passage that they can’t play. When you just take one measure, you take two or three minutes and just walk them through in different rhythmic figures and I say ”ok, now play the whole thing” and it’s like magic, they can play now what they couldn’t play three minutes ago.

When I learn new music that doesn’t have a pattern that I’m familiar with, unusual chords, and arpeggios and scale pattern, when I do that, even an old man can learn new tricks (laughs), when I can’t sight read it.

Healthy aspects of practicing

DS: Practicing is working out problems. I feel better always after a good practice.

HM: It is hygienic, mentally.

DS: I think maybe physically too, not the muscles so much, but the breathing, I think it’s very good, the breathing. Substitute for Yoga.

Relaxation

HM: I have to practice a lot, every time, always! Do you speak about relaxation, like Keith Stein[2], who wrote a whole chapter about it? He has a good exercise to tense all muscles for a moment, and then relax them, and then play.

DS: You know, I have got to look at that book again (laughs). But I think that there has to be a balance between relaxation and preparation, but to have everything engaged, which should announce really being tensed in some ways, and poised to use all the mechanisms, but if you start out to tense, then you won’t be able to breathe and your fingers will be locked up.

HM: It depends, maybe on the personality of the students.

DS: You know, there are so many schools! Do you know Aude Richard-Camus? She is the Director of Lancelot competition in Rouen. She was a student here and she studied also with Michel Arrignon and she studied quite extensively the Alexander Technique and she has written articles [1] as a whole school of playing where she incorporates body awareness to certainly relaxation but mostly, I think, efficiency. I think, relaxation, meditation is great but when you’re performing, it’s the meeting of the two and the relaxation is the preparation to be able to use the right kind of tension.

HM: Finally, it’s the musical idea that guides performance?

Intonation

DS: I’m in favor of intonation (laughs).

HM: It’s a question of finding the right voicing first of all and when necessary, finding some special fingers.

DS: Sometimes, but I always try to find the voicing that works before I try to find the fingering. But it’s different, you know, every instrument has slightly different pitches, especially the altissimo and then the lowest register, but you know, selecting an instrument and equipment is also very important: that the 12ths are accurate.

HM: I know; lower notes. I’m playing a Wurlitzer-Boehm with a lot of keys and holes and the bore is so wide, so that the 12ths in the left hand have a tendency to spread.

DS: Are they too wide?

HM: Yes, too wide, specially b’’ and c’’’! But if somebody else pushes the register key when you are not prepared to change the register, then it’s much better, quite in tune!

DS: That’s right. I think there is a lot of over compensating. I’m playing a Backun Lumiere clarinet now and I find the pitch very good. But you know, the player has to play in tune, the instrument doesn’t make the sound by itself. And I find the 12ths are pretty good.

HM: It’s a question of the bore. I know a very good instrument maker; he makes historical instruments and knows a lot about instrument tuning.

DS: This is the man in Bern?

HM: Yes, Andreas Schoeni in Bern controls the whole bore, going up into the mouthpiece for the 3rd register. When I play, he measures the bore inserting a stick, on the top a little bit thicker, into the bore. Each note has its specified place in the bore, where a constriction or extension changes the intonation of the twelfth and of the third above the double octave (third register).

DS: It’s amazing how these things make a difference. (Clarinet Tuning and Voicing with Morrie Backun and Ricardo Morales:[2]

Staccato alwasy backed off by the wind

HM: Do you teach double tonguing?

DS: I have never been able to master it. I can do just fine on one note, but I can’t really get control of the speed enough to coordinate with the notes. I have many students who do it beautifully and I say: “can you teach me?” I’ve had to get along all these years with single tongue, for the most part.

HM: Very good.

DS: Ricochet violin technique sometimes, you know, using the wind to let bounce the single tongue off the reed but not doing ta-ka-ta-ka-ta, but trrrrrr and they work for some things.

HM: So it’s not flutter tongue?

DS: No, no, and it’s just “trrrrr” and it’s totally dependent on efficiency too and the tonguing being really close to the reed and the air stream moving fast, so that the tongue can balance back.

<br

HM: Ricochet, but single tonguing.

DS: Yes.

HM: It’s like so quickly as a ball not really controlled but very quickly rebounding

DS: Yes, and bouncing. It works especially with this series of repeated notes, something in Nielsen Concerto, to get it up, close to the tempo.

HM: And still the possibility of the velocity is linked to the air flow.

DS: I think so. if there’s a thing that’s working efficiently, to keep the tongue close and strong without tensing up and trying to overkill.

HM: And important: move the tongue in a small motion.

<br

DS: Small motion, small but definite motion, and always backed off by the wind.

Reeds

HM: Do you work on reeds?

DS: Not anymore, I play Légère plastic reeds, two or three years now.

HM: They’re getting better and better.

DS: Oh, they’re really good now. You know, I had an interesting experience. You know Corrado Giufreddy, the Italian player?

HM: Not personally, but yes, I know him.

DS: He was visiting and he had some and said: “Try these” they’re better than I thought I couldn’t really feel that comfortable. Then, I ordered some and I tried different mouthpieces and I found that I couldn’t use them with my existing mouthpieces, but on some mouthpieces, it worked quite well. Then I went to a rehearsal, we were doing Mozart c minor Wind Serenade. I just didn’t tell anyone but payed on plastic reed. Then I ask the oboist: “was it ok, playing in tune today, it sounded ok?” He said “Yes! It was really good and the tone quality was better. Do you have a good reed today?” I thought “Ok, this was worth trying.” I had some downs, and I had some back and forth with cane. That was 2016 I think. I recorded the Nielsen Concerto that summer. I know, in the performance, I used cane; then for the recording sessions, for patches, I used plastic. The recording came out from the live concert, but we did some inserts from the recording sessions. I can listen to the recording myself and I can’t tell which is cane and which is plastic.

HM: I have to try it again. I tried, but I couldn’t get along with the intonation at the opera. Maybe it was too soft.

DS: You know, sometimes the higher registers are a little lower. It’s a little different

HM: Maybe, as you said, I have to look with another mouthpiece. I use it for the contrabass clarinet. When it gets dry, it becomes quickly difficult with cane.

DS: It’s nice also when you’re doubling. I use it on E-flat and bass clarinet if you’ve to go back and forth. I did some Pierrot Lunaire performances, I never worried if it’s dried out.

HM: That’s really an advantage, yes.

Warmup

HM: Do you advise your students, to do regularly special warmups they should follow? With scales, long notes, staccato?

DS: Sure. The warmup I told you earlier where I start with low E, half steps (e-f-e-f#-e-g..). And, if I have time, I play this through three octaves. I try to do the same exercise maybe starting in the middle register. And almost every day, when I start I play the circle through all the major and minor scales, the way Klosé did it, with harmonic, I mean melodic, minor and you just go from, C major, a minor, F major, d minor, going through the circle and it comes back around. And it takes a few minutes. I try to play evenly, to match the sound and registers.

HM: In slow or fast tempo, or both?

DS: (sings the tempo) Moderate. And sometimes after, I do it again faster.

HM: In combination with articulations, with staccato.

DS: Yes, I mix it up.

HM: Not first of all only legato, then staccato - It can take so much time…

DS: And it is diagnostic too. If I find that a connection is not working, then I slow it down, see what’s wrong.

Conclusion

HM: What would you say to which tradition of clarinet playing do you feel the most attached? Could it be said that you feel closely connected to the old French school? Or do you find today that you had much other important and different influences?

DS: So many influences, but I do think that so much of what I rely on comes from that old French school and what I have learnt from all these different students [of Bonade and McLane].

HM: Could you say, that the most important thing concerning the old French School, is the know-how about double lip embouchure?

DS: Yes, sure, voicing! It’s voicing.

Key issues: voicing, support, embouchure

HM: Voicing, it’s a key issue.

DS: And using the way to really support the sound, and I find that when something is going wrong—note doesn’t speak, interval doesn’t work, articulation doesn’t happen—that the first place I go is to open up more [the embouchure], use less pressure on the reed, and rely on the wind (ware? 1.01.34). You know, different teachers express the very same things in different ways.

HM: Yes. I think we are through. Thank you very, very much for this interview!

DS: Did you turn that on? (points to the recording device, laughs). Yes, I see the light!

HM: I think it worked!

References

- ↑ 1,00 1,01 1,02 1,03 1,04 1,05 1,06 1,07 1,08 1,09 1,10 1,11 1,12 1,13 1,14 1,15 Paddock, Tracey Lynn, and Frank Kowalsky. 2011. A biographical dictionary of twentieth-century American clarinetists. Treatise (D.M.)--Florida State University, 2011.[3]

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 Stein, Keith. 1958. The art of clarinet playing. Evanston, Ill: Summy-Birchard.[4]

- ↑ Spahn, Claudia, Bernhard Richter, Johannes Pöppe, and Matthias Echternach. 2013. Das Blasinstrumentenspiel physiologische Vorgänge und Einblicke ins Körperinneren. Innsbruck: Helbling.[5]

- ↑ Bonade, Daniel. Clarinetist's Compendium including method of staccato and art of adjusting reeds. Kenosha, Wis: Leblanc Publications. [6]

- ↑ Bonade, Daniel. Clarinetist's Compendium including method of staccato and art of adjusting reeds. Kenosha, Wis: Leblanc Publications. [7]

- ↑ Bonade, Daniel. Clarinetist's Compendium including method of staccato and art of adjusting reeds. Kenosha, Wis: Leblanc Publications. [8]

- ↑ Guy, Larry, and Daniel Bonade. 2007. The Daniel Bonade workbook: Bonade's fundamental playing concepts, with illustrations, exercises, and an introduction to the orchestral repertoire. A Bonade Workbook