James Campbell

The interview with James Campbell was held 2019 November 6th, at Neuchâtel, Switzerland and has been edited by Heinrich Mätzener.

Studies

HM: Where did you study, and who were your teachers?

JC: When I was in high school, I studied with Ernest Dalwood, who was English and came to Canada in a military band and played in the orchestra near where I lived. He had studied with Frederick Thurston and was, in a way, very English. At that time he played Boosey and Hawks clarinets but didn't make me play them, I played a Selmer clarinet. He was my first teacher and got me started on the right path. Out of high school, I entered a competition in Canada, where [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Marcellus Robert Marcellus] was one of the jury members. After the competition, he gave me a lesson, and I remember him talking a lot about the air column and other basic things. I then went to the University of Toronto. I studied for four years with Avrahm Galper, who was then solo clarinet with the Toronto Symphony, and who had also studied with Frederick Thurston in London. But I think more importantly more for him; he studied with Simeon Bellison in New York. So a different kind of idea coming came from there, the Russian school.

I spent a summer with Daniel Bonade and a couple of summers with [Michell Lurie Michell Lurie] and George Silfies, all quite different, but from the same French tradition. Looking back, Bonade was the most influential. Mitchell Lurie, who I enjoyed, taught me a lot about the importance of the clarinet as a melodic instrument and George Silfies was one of the most rounded musicians I have ever met. Then I heard Yona Ettlinger, a good friend of Avrahm Galper, and I knew I needed to work with him, so I went to Paris, where he was based at the time. I took private lessons in his flat. On my way to Paris to study, I entered the Jeunesse Musicale Clarinet Competition in Belgrade and ended up winning it. This led to me getting offers for quite a few concerts and, being immature, I must have thought that I was really something ( laughs), But I will always remember my first lesson with Yona Etlinger, who was known to be tough. Still, at that lesson, he was very friendly.

Learning and teaching

JC: At that first lesson, Yona Ettlinger congratulated me on winning the competition and then talked about embouchure muscles. He gave me four notes: F, E, Eb and D to play as long tones and spoke about strengthening the lip muscles, particularly the upper lip, and how to see that it looks good. He then said not to play anything other than those four notes until the next lesson. Which was to be in three weeks!!

HM: And you were still very young?

JC: I was twenty-one. I almost did it. (laughs) I stuck to it for 95 % of my practice time. I realized later what Yona was doing with me as a young kid who had just won a competition and must have been full of himself. He was getting me ready to learn. That was such a wise thing to do. I was alone in Paris. I didn't know anybody. I just stayed in my little room and played those four notes(laughs). And of course, exploring the streets of that beautiful city. When I came back to the next lesson, I was once again a student, and I was ready to learn.

HM: But you really did it, you played only these exercises?

JC: Yes, and to this day, long tones help give me solidity in sound production.

HM: Three weeks in a whole life is not that long time.

When you're ready to learn, the master appears

JC: I was learning all that time, I was learning discipline, and learning that there are no short cuts, no jumping ahead. And I finally realized, what Avraham Galper had been teaching all along, and what Daniel Bonade and Mitchell Lurie had been talking about: that it takes small, consistent steps at a time to build a strong base. Ave Galper used to say: do this, it will keep you in business. Now, 50 years later, I am still playing (laughs)!

HM: And you still do your tone studies every day? Long notes, and so on?

JC: Yes, every day! [mimes the embouchure forming: upper lip down, flat chin, corners of the mouth inwards]. And I have told the story about playing those four long notes many, many times to my students.

HM: And with your students, did you also make them play only four notes, for two weeks?

JC: No, nothing quite as severe as that, but they do many tone studies. They also have to prepare repertoire for competitions and auditions, you know.

There is a Zen saying: "When you're ready to learn, the master appears." And boy, is it true! When you are teaching, you can be talking to somebody, and you know they're just not hearing what you are saying. And then later on, sometimes a few years later on, they may finally understand"! That's how we all learn, and it's just normal. I make them take notes and ask them to contact me when they finally understand what I am saying to them. Sometimes I get an email several years later saying that they now "get it!"

Playing for other teachers is also very valuable.

I had a student, and we were working for a long time on breath control. One day she went to a masterclass with one of my colleagues and came back saying: "Oh, you should hear what I learned, "and went on to repeat what we had been working on for the past year. That's the value of masterclasses.

Toolbox

JC: I try to fill a student's "toolbox" with technical and musical tools they can use to fix any problems that may come up. If they have the right tool, hopefully, they can fix the issue.

HM: The principle is to mention or write a small word in their notes, which triggers a more complicated chain of thoughts and the correct automatic muscle activations necessary for a particular passage?

JC: Yes. My class calls them Campbellisms; I call them tools.

For example, GAB is an exercise that helps voicing, (G is open G, A is throat A and B is long B). Done correctly many times, the tongue will eventually find its correct position when these notes are only heard in our inner ear.

HM: Did you write them down?

JC: The students should! (laughs). Ultimately, our goal as teachers is to make ourselves not needed anymore.

HM: And I think these tools can be interacting: a breathing tool can improve the articulation or the finger technique.

JC: Yes, everything influences everything. But it all takes time.

And when one day when the students are teaching, they hopefully will use these tools and develop them even further. I find that very exciting.

Practicing

Warmup for athletes with small muscles

JC: The idea behind a warmup is: we play with muscles. Athletes warm up their muscles. Musicians are called "athletes of the small muscles." So, what muscles? Embouchure, tongue, lungs, ears, brain, fingers. I use Avraham Galper's (2001) book "Tone, Technique & Staccato" It covers everything, starting with the air, then fingers and tongue. When I feel that each is ok, I leave to move on. Some days it seems to happen immediately, other days can be a struggle, but it is crucial to cover each muscle every day. I remember what Yona Ettlinger said and how he made me focus and concentrate because the essential part of the warmup is the brain. Students are busy the whole day, as are we. If your time is limited, the exercises in Mr. Galper's book are wonderful.

Keep the brain going when practicing

JC: It's possible to practice and get worse - you can be practicing the wrong way, not concentrating and examining what's right and wrong. Every time we do an action, we make an electrical connection, and myelin wraps around the nerves, strengthening that connection. Every time you do something incorrectly, you are making a faulty connection. I don't know about you, but when I was young and stupid, I did some things the wrong way, and to this day it bothers me. Other things I happened to do right and to this day, I feel confident approaching them.

If anybody dreams of spending their life in an orchestra, they absolutely must practice in the right way, especially the solos. They are going to come up again and again, for their whole life. So if they have practiced in the right way they can have a happy life, if not, they will struggle. And all that happens in the early stages of learning. So, the teachers have the responsibility to make sure that their students learn how to practice correctly. It can be a real challenge!

HM: I see this in my work. When I have to learn a difficult contemporary piece, it is still challenging to find the right techniques to work on it. That I don't ride off carelessly, overlook mistakes.

Maybe, when we are learning something, combining the movements with tasks on different levels, like standing on one leg and making an eight tour with the other, while playing difficult passages?

JC: It keeps the brain going; it's excellent. If we are working correctly, the mind should be tired before the embouchure.

Fun and work

JC: Having fun is a part of practicing that I think students miss sometimes. There are two parts that I ask them to explore. One is realizing they are a professional student whose job is to practice. For example, I say look at the person working at the check-out counter in a store. They are working and may not be enjoying their job. But it is a job, and their role as a student is to practice, it may not be fun, but some things have to be done. They are professional students!

But we also PLAY music, and we play the clarinet. So make some time to play. Relax, play pieces they enjoy, improvise and explore. It's a fact, if they want just to play, even make funny noises( laughs), but are not concentrating on it, they will not teach themselves any bad habits. But building serious connections between the brain and muscles takes tremendous discipline. And again, I return to those four notes (laughs) [F, E, Eb, D] I had no clue at the time, but the wisdom of that discipline stays with me always.

Building up the embouchure

JC: Yona Ettlinger and Abe Galper taught the strengthening of the upper lip, bringing the corners of the mouth in and pointing the chin. The regular clarinet embouchure. It is imperative to have the time to think about and focus on the embouchure. Abe Galper (2001) wrote a book called "Tone, Technique & Staccato," and it is just that. It's just solid exercises, nothing fancy. All my students play out of that book, and I tell them: "If you can play everything in this book, you can play the clarinet." and you will stay in business for a long time.

It follows the theory that the richer the low register, the better the upper register sounds. You first learn to produce a good, full sound in the chalumeau register, then transition to the clarion, and finally to the top, all the while incorporating the staccato, legato and correct fingerings.

HM: Coming back to the embouchure and Yona Ettlinger: he was a student of Louis Cahuzac, who was a double lip player and represented the old French School. He played differently than Ulisses Delecluse.

Different playing in the 1970s

JC: Oh, yes, at that time, Delecluse was at the Paris Conservatoire. He represented the French style, much like Jacques Lancelot and others. In 1970, while a student at the University of Toronto, I entered a clarinet competition in Budapest. Mostly to play, but also I listen to everybody. At that time, as you may remember, there were significant national differences in playing. The French, Germans, British, American and eastern Europeans all had very different concepts of how to play the clarinet.

HM: Some players used a vibrato, fast and always with the same frequency. Some used to play also very loud; the Czech style at that time was very loud.

JC: Yes, brilliant clarinet playing!. The German sound was round and dense, and the French quite compact. What a lesson that experience was!

HM: Today, there are less different styles; worldwide, you can hear more or less the same sound.

JC: I would call it "MidAtlantic," a sort of international sound. The differences are there, but less noticeable, and the technical level of playing has gone way up.

Double lip, the perfect embouchure

HM: Do you use, maybe only as an exercise, to play with double lip embouchure?

JC: I think that the double lip is the perfect clarinet embouchure.

I get my students to do it in practice. I want them to develop what I call "a double lip embouchure without the pain." Everything is the same, and you just don't have the upper lip under the teeth. It's a fantastic way to build up the embouchure with the lips and find the right form inside the mouth. Yona Ettlinger was teaching this when I worked with him.

HM: A good friend of mine, Michael Read, clarinet solo in the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, was a student of Yona. He also told me that he had to do exercises with double lip embouchure. Both our teachers, Hans-Rudolf Stalder and Yona Ettlinger, went in the summertime to have lessons with Louis Cahuzac, where they were taught this embouchure technique. We had to play long notes with double lip embouchure, to learn not to bite and to learn to vocalize.

JC: Yes, it raises the tongue and lifts the back of the palate.

HM: The most difficult note to play with double lip is the high c3, there is a pivot, pressing the mouthpiece against the upper lip.

JC: Yes, it moves [there is no stability holding the clarinet]. I never performed with double lip; I just use it as a tool. But it is the perfect embouchure.

HM: Did you take lessons with Kalmen Opperman? He wanted all his students to play with double lip.

JC: No, I didn't.

HM: It is in the tradition of the old French school, the old methods (Hyacinthe Klosé, Pierre Lefèbvre Prosper Mimard) taught a double lip embouchure.

JC: They played with double lip, yes.

HM: I wonder why this has been changed in the French school.

JC: When I was with Daniel Bonade for a while, we didn't do any double lip. He talked more about the high tongue placement and using fast air. We covered everything that is in his books. Lots of Rose studies for fingerings, staccato exercises, legato practice. It was great!

Athletes of the small muscles

HM: Do you try to explain all the details of the embouchure and the voicing, or do you just give the students soft reeds and let them find themselves the right way of tone production?

JC: Oh, Yes! But it depends on the student's needs.

Do you know Larry Guy's books [1],[2],[3]? In his books, Larry Guy has brilliantly summed up what many great American teachers have been teaching. For example: how to put the clarinet in your mouth and how to get equal pressure around the mouthpiece. (See also Larry Guy—Fundamentals of Clarinet Performance)

A few of his students auditioned at our school, and they all knew what to do.

'HM: The embouchure should not be formed from down to up, but from…

JC: From side to side, yes. It is called the "Marcellus triangle," which is a point here (a formed dimple in the chin), here and here (both corners of the mouth) [4]. And use a strong upper lip: we call that: "Mister Marcellus with a mustache," a simple picture so that students can remember.

HM: Do you do teach embouchure also without the clarinet?

JC: Well, specific callisthenics help build lip muscles. The firmer the muscles, the less we bite. Musicians are often called athletes of the small muscles.

Voicing

HM: What would you say, why is voicing so important?

JC: I think it is central to control and tonal flexibility; it is fundamental to getting more reeds to work; it is central to intonation, of course. And one exercise I have done with a lot of students is to have them play with no embouchure and try to focus the sound only with the tongue. It's amazing how that can work. They are often surprised how high the tongue has to be set in the mouth to get fast enough air to focus the sound.

HM: With whom did you learn this? Or did you find it by yourself?

JC: I think every teacher I ever worked with talked about this.

HM: I heard about this method; I think it was an English clarinetist who used to teach that. I think the difficulty in voicing is also that we are forming a vowel with our lips, something like a mixture between "e" and o, but the tongue has to take the position of different vowels.

JC: Yes, the students have to learn that; it's hard.

Fast speed of air

JC: To make the clarinet work, it needs fast air. We raise the tongue, so the air goes fast, like air flowing over the top of an airplane wing. It's incredible how many students don't want to do that.

HM: For what reason?

Bright or dark?

JC: They don't like it. Because up close, it sounds thinner and brighter, and they want big and dark sound and don’t realize that the clarinet sound very different up close. A seemingly bright sound up close translates into a full, dark sound in the hall.

HM: It's a fashion of today to play like that.

JC: Yes, all my teachers taught that fast air gives a full, rich sound. I have been struggling with students for years. Some get it right away, but some others won't believe me. I guess most clarinet teachers have the same "battle" with some students.

The sneaky brake between g2 and a2

HM: Do you change the vocalization when you play different registers, high or low notes?

JC: Well, the tongue does change. The highest position of the tongue, [the smallest distance between the tongue and hard palate], changes [between its tip and a point about one centimetre back from the tip] (shows with one hand the curve of the hard palate, with the other hand the position and form of the tongue.) We call it the sneaky break between g2 and a2 (he sings the beginning of the Mozart concerto, first measure). That a2 never seems to want to work, it's always flat [or it's difficult to get with a beautiful colour]. It never would work well if you don't' slightly adjust the tongue position between g2 and a2. I teach my students that this is a break in the clarinet that looks so easy that we call it "sneaky." The back of the tongue starts to drop and stays that way from a2 up to about f3. It is slight, but it happens. By the way, this is why double tonguing is challenging in that register. There is another break when you go between f3 and g3, that's where the back of the tongue goes back to its" normal" high position.

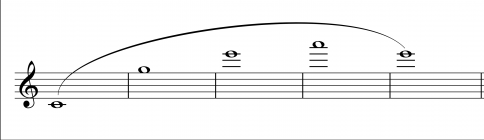

In Galpar's book register changes, we talked about, see how that works:

EXERCISE

Exercise for the toolbox #1

- Play c1

- play g2 the twelfth above,

- then e3.

You find that to get the e3 works better when your tongue is dropped a little bit in the back.

- And then, to go up to the a3 you will need to bring it [the tongue] back up.

So, you start to feel that motion.

With my students, we call the tongue the "eleventh finger," and if you get used to that, you get a lot more control. When you play fast, it goes [without special effort]. But when you have a slow legato like in the first phrase of the Copland Concerto when it goes up to the high e3, you can control it by being aware of the movement of the tongue. I tried it with my students a lot, and it takes time to learn.

HM: I try to show this by putting my fingers at the base of the mouth, then pushing them slightly away.

JC: Yes, you feel it.

HM: On a daily basis, you could compare it with the situation where you have to yawn, but nobody should see it. But in this description, the special position of the tip of the tongue is still missing, which should extend forward, upwards to the hard palate.

JC: Yes, that is what Keith Stein (1958)[5] talked about in his book "The Art of Clarinet Playing: yawning. He was in the orchestra, sitting in front of the conductor and not wanting him to see him yawn. (There is no biographical information aviable about Keith Stein. As source consult David Pino (1980), The clarinet and clarinet playing [6])

Mastering the brake – downwards!

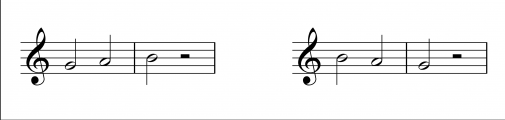

EXERCISE

Exercise for the toolbox #2

JC: I found a little exercise that I give my students that is terrific for that:

- You play open g', a' and then b.'

- When you hit the b: I ask, "did you notice the tongue doing something?" ( most students will notice a tiny movement)

- I then say:" good, it should move! The clarinet is pulling the tongue into the right place!"

It's a fantastic thing! I make that part of the warmup. And when you are tuning, don't play only your b', play g' - a' - b.'

I have always tried to find little things that have an impact on me and for my students. This exercise is not hard to remember and not hard to do; the clarinet immediately shows you where the tongue has to go. It's because of the backpressure,

- The key is going back down:

- b' - g' - a'

- There is a tendency to drop the tongue when we descend over the break, this exercise helps us become aware of that. We have to consciously keep the tongue in its proper position.

Most of the time, students get a better sound on the g' when they come back down. I call that a tool for the toolbox.

I don't remember who taught m that exercise came. But I use it a lot.

HM: Often, if they come down from the upper register, like in the solo for Eb clarinet in Ravel's Bolero, the a' and g' doesn't vibrate freely and tends to be too high:

JC: That happens if the tongue drops and the air support lessens. The throat notes sound louder to the player because they are close to the ear, the long tubed notes, like c, b' are further away so seem softer. Therefore we tend to back off the throat tones, making them softer and sharper to the listener.

Articulation and Staccato

HM: You talked a lot about voicing. When the tongue is in its right position, articulation is much easier.

JC: Yes, the right speed of air makes the reed vibrate. For clean articulation, you need to make the reed vibrate immediately. Fast air, which makes a good, ringing sound clean articulation. If that is in place, we then need to find the right spot on the reed for the tongue to touch. Everybody is built differently. I don't believe that there is only one way to articulate.

HM: It also depends on the music and from the context, maybe…

JC: And also how you are built. Mitchell Lurie once told me: "I never touched the reed in my life." He touched his bottom lip.

HM: I heard about this technique from French clarinetists; Alain Damiens, his teacher, taught him not to touch the reed, but touch his bottom lip with his tongue.

JC: It works; I use it sometimes. There was a student at Indiana University who used this technique and tongued faster and cleaner than anybody [blrup, imitating him]. I wasn't going to change him.

HM: But usually, you touch the tip of the reed with the tip of the tongue?

JC: Normally, just below the tip of the reed with just behind the top of the tip of the tongue: I try this textbook way with each student. And if it doesn't work, I try something else.

HM: Do you use the exercise Nr. IV from Paul Jeanjean's (1927) Vade Mecum "Détaché"?[7]

Our Teacher, Hans Rudolf Stalder, wanted us to stay first with the tip of the tongue at the tip of the reed, start to blow, and let the reed vibrate. Only after the reed vibrates, release the tongue from there and touch it quickly and easily, like a reflex, again. I think he learned that with Louis Cahuzac. It's also an excellent exercise to learn air support, and an exercise to have an embouchure without biting.

Sometimes, I also touch only a corner of the reed, it's easier to control.

JC: We were also trying, somebody mentioned it, to move the tongue not up to down, but from left to right. It works, I am working on it now. When you are older, your tongue is supposed to slow down. But in this way, I can go faster than before!

Double tongue

HM: You also use double tongue?

JC: Yes, I do, but not often. I don't triple tongue.

HM: What's the most important thing to get a good double tongue, especially in the high register?

JC: Oh, that's hard. But you can't do it in the same way. The reason is that the back of the tongue is down, right? And you can't get the same fast air. Peter Clinch, an Australian Saxophone and clarinet player, could double tongue everywhere. He showed me how to do it in the upper register by placing everything more forward [imitates motion and sound of double tonguing "ti-gui-ti-gui"].

HM: The tongue moves more in front?

JC: Yes, more in front, not switching it back. I tried it, but I haven't practiced it that much.

Two ways to learn a short staccato

HM: Do you use the exercises "fingers ahead" to get a clean staccato and proper coordination between tongue- and finger movement?

JC: Yes, it gives a very clean staccato. It is hard to do at first, but it helps.

I learned this technique from Daniel Bonade, who also taught the staccato from a short note to a long note. Another of my teachers, Abe Galper, went from a long note to a short note, using a very light tongue which gradually rests longer on the reed, making the notes shorter. Both arrive in the same place, a clean, short staccato. So, in my teaching, I have used both, depending on the students.

HM: It takes a lot of time. So, it is quite tough to give a student a soft reed and tell him: "go home, practice with this reed and come back with a good result with a nice sound."

JC: It does work.

HM: I let them sometimes play for some week's bass clarinet or even on a historic clarinet. On these instruments, it is not possible to play with hard reeds, the fork fingerings wouldn't work at all. You are forced to find a way. And as the weight of these instruments is lower, they are easier to play with double lip, because they are not turning against the upper lip as the modern, heavier instruments do. It nearly does not hurt playing double lip.

Breathing

HM: How do you teach breathing and wind support?

JC: It is pretty standard, I mean it's what everybody has to cover, that the clarinet works. I also like to ask: "tell me how the clarinet works!" They tell about vibration and so one. I say: remember this: "It works when you blow into it." If I have a problem, maybe I am not blowing correctly. It's fantastic how many times that fixes a problem, There are a lot of theories and exercises, but the primary thing is we make music on the clarinet with the air.

Support more when playing piano

JC: If you have to play louder, you blow more. If you play softer, you don't blow less. You support more.

EXERCISE

The breathing - tool b – b – b

JC: I have a "tool" for breathing; it is simple. and we call it b - b - b -. It means belly-button-breathing. I found that they pretend to breathe in through the belly button, and then pretend to blow out "through the belly button" it activates all the breathing muscles. When I want to be sure to have really good support, I write b - b - b. in my music. It's an easy thing to remember.

Holding the clarinet

HM: How we should hold the clarinet often does not seem to receive the attention it deserves.

JC: It's a big issue. If not held correctly and firmly, the clarinet can fall out of the mouth. I have sometimes pushed the clarinet upward into their mouth while they are playing, and the sound immediately improves.

HM: Do you also use holding the clarinet as part of the embouchure? Instead of biting with the jaw to make the little, necessary pressure?

JC: I ask my students to "plug" the clarinet into their mouth, firmly but gently.

HM: As I know, it was the old French school to play that way.

JC: There was a student in a class who wanted to know the "secret to good clarinet playing." I answered, "Leave it in your mouth!" Meaning keep the instrument comfortably "plugged into your mouth," especially when playing descending scales and arpeggios. It's incredible how that works!

HM: Do you change the position of the mouthpiece in your mouth, when you play louder, you take bit more mouthpiece in your mouth, when you are playing softer less?

JC: Yes, I sometimes do that.

HM: It is also possible to start a soft note only by taking more and more mouthpiece in the mouth, after having established the airflow.

The angle clarinet - body

JC: I use this for the balance. Recently, just in the last few months, I am bringing the clarinet in closer to my body. You can then really relax the jaw.

Daniel Bonade held the clarinet close to his body (I didn't see him play, I only saw it on pictures) - with the clarinet firmly in the mouth. And he used fast, focused air, created by the high tongue position we talked about earlier. When you do that, the sound absolutely sings.

HM: He played holding the clarinet very near his body.

JC: Yes. he taught me that, and I now finally understand! (he laughs)! It is now pretty standard teaching.

HM: It should be a unity: breathing, voicing, embouchure.

JC: All in one, I agree.

HM: And also holding the clarinet. Holding the clarinet is part of the embouchure.

Position of the thumb rest

HM: I try to stabilize my thumb by training the muscles. But I also changed the position of the thumb rest. What do you think, what position should the thumb rest have

JC: The hand should be in its natural position. I tried different thumb positions for a while but found that the best balance is found when the thumb rest is between the index and third finger.

HM: Often, the buffet clarinets put the thumb rest much lower.'

JC: They put it way down. I also changed the position. I hold my clarinet nearer to the body, which brings the wrist in a straighter position. Because my fingers had to come back, I've had a repairman adjust the screws for the thumb rest and linkage keys. It feels, sounds, and plays much better. The fleshy parts of my fingers are getting the centre of the holes.

HM: Do change the thumb rest also for your students? So that their fingers are all a bit curved when holding the clarinet?

JC: I check it out, yes. The form of the hand should stay natural; relaxed! It is a challenge sometimes to achieve this.

HM: I think that the form of the thumb determines the form of the other fingers. When the thumb and index form the letter "C," the other fingers are also curved.

JC: Agreed! There are certain things you have to watch every day: such as checking the tension in the hand. A teacher can say "just relax," but there are things that you have to be aware of every day. We musicians are called athletes of the small muscles, so we have to warm up well and always pay attention, so tension does not work its way into our bodies.

Get the basics, but also find your own character!

HM: I think it's a difficult mission, to get the students at a point, where they find their character and personality in playing. We always make a lot of corrections, say do this and that. It's dangerous that they don't lose their self-confidence.

JC: That's the whole other side of teaching. I try very hard to get them to believe in themselves, but it has to be based on artistic truth. They must be trained to value good taste and quality.

Daniel Bonade (1952) took the slow Rose studies, edited as Sixteen Phrasing Studies for Clarinet. They are fabulous. I have the students play those studies with Bonade’s phrasing marks, precisely as he wrote them. For example, if the crescendo starts on the second note of a phrase, they must start the crescendo on the second note"; This requires super discipline. Sometimes a student will say, "How can I be musical if I have to be so disciplined?” I’ll answer,” You wait, you will see.” When they finally do it properly, they sound beautiful. Once they understand the concept of good phrasing, I tell them to change the markings, do what they tell themselves to do, but with good taste.

HM: So, they have to start to think about their musical creativity.

JC: They have the basics of proper phrasing and the discipline to play what's on the page.

Vibrato

HM: Do you play with vibrato?

JC: Yes, I use it as a colour. I like to use it, but I always try to get a characteristic clarinet sound. The clarinet, I think, is the most colourful woodwind instrument, it is used in folk music and jazz! So in the early stages of teaching, I want my students to get a focused, solid, and very characteristic clarinet sound. It has to first be very solid, like Yona Ettlinger's playing. And once you have that and your ears work correctly, you play folk music, chamber music, contemporary music and jazz. You can change your colour, but you don't lose your solidity.

HM: And how do you produce the vibrato? By moving the jaw, the tongue, or the vocal tract?

JC: Yes. The vocal tract. I believe that it is important to have a characteristic sound that can also be controlled. Of course, we must find our personal sound. I don't want my students to sound all the same. But it has to sound like a clarinet!

At Indiana University, my colleagues Eli Eban and Howard Klug

We were all different players, came from different backgrounds, had different values, but we all agreed that a clarinet has a characteristic sound. We formed the Trio Indiana [8] and performed many concerts and recordings together. We all had our own sounds, but when we got together, we ended up sounding the same. It was an ideal situation. I hope our students picked up something from that.

Intonation

JC: Intonation is ear training and control; you have to hear if it is sharp or flat and make the necessary adjustments.

It is about training the ear to be continually listening for intonation.

HM: Yes, if you would always sing with your inner ear.

JC: Yes, that is one reason we have slow studies, to get students to hear the pitches and the tonality. The saying, "if you can't sing it, you can't play it," is so true.

HM: A sustained note, the keynote or the fifth of the basic harmony, played by the tuner...

JC: …Playing the Kroepsch studies over a drone and stopping on a unison or a fifth to check pitch is a good exercise.

HM: Do you change to the right intonation by modifying your tongue position?

JC: Yes, and a slight pulling the instrument away from the mouth can help lower pitch at times. But relaxing the jaw and focusing the sound with the tongue can also help adjust the intonation, just keep it the air fast. I think that would help blend in an orchestra chord. In solo playing, it's a little more difficult because you need to keep and steady embouchure and focused air.

HM: If you are playing with piano, do you play the thirds like a natural interval, a bit lower than equal-tempered?

JC: I find I have to go with the piano. We are used to hearing the sharp thirds when the piano plays alone and often finds ourselves in unison with piano on the third of a chord. The Schumann op73, the last movement is a real challenge for this reason.

Alfred Prinz in Bloomington

HM: Alfred Prinz was also living in Bloomington?

JC: Oh yes! For many years. He became the fourth member of our group of professors.

“Freddy” was the first classical clarinet player I heard. I grew up in a town in Northern Canada, on a farm. So, my exposure to classical music was limited. I thought the clarinet only played jazz and started out by playing some Jazz. My uncle gave me an album and said: you should hear this, classical clarinet music. The player is from Vienna so he must be pretty good. Of course, it was Alfred Prinz playing the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. I listened and was very impressed.

Many years later, he moved to Bloomington, and we became friends. He was the first classical clarinet player I heard playing solo repertoire and was so happy to have him autograph my copy of his recording.

When he lived in Bloomington, he didn't play very much. He painted, sometimes he played with us( Trio Indiana) and wrote several pieces for us. When he played, everything looked wrong (imitates his posture), but everything sounded right. That was an excellent lesson for the students. It made the point that if a student hears the sound and gets it planted in their ear, somehow, they'll get it. But if they don't hear it, even perfect posture will do very little good.

In the end, We play clarinet and make music by ear!

HM: Didn't he also work a lot on reeds and mouthpieces?

JC: We never talked about equipment very much, perhaps because he was retired and didn't have the stress of his former position at the Vienna Philharmonic. He really was a great musician.

Compositions by Alfred Prinz

HM: Hanstoni Kaufman, a former student of Alfred Prinz in Vienna, got all his manuscripts from his widow. He lives in Lucerne.

JC: My colleague at Indiana University, Howard Klug, has a publishing company, and I wouldn't be surprised if a lot of his works had been published by his company. I think he published all of his music. The music for clarinet, the trios, are very nice, but quite tricky!

Reeds and Mouthpieces

HM: What Reed and mouthpiece would you recommend?

JC: Vandoren is excellent; they are doing great work for students and professionals. Right now I play a Hawkins, I have several and use them all and have for the last five years. I also have some old Kaspars that I got from Ave Galper almost 50 yrs ago! They are outstanding.

Légère Reeds

JC: I use Legère reeds. I have learned how to use them.

HM: And do they work with a Kaspar mouthpiece?

JC: No, they didn't at all. But Ramon [Wodkowsky] worked on one of my Kaspars and got the reeds to work on it.

HM: Ramon works on the mouthpiece, not on the reed.

JC: Yes, He knows how to make a mouthpiece work with Legere reeds.

HM: Does he change the surface of the table, a bit rougher, like Playnick in Vienna does, as I heard?

JC: No, I don't think so, I don't know what he does, but it works!

I have been using Legere reeds for over 20 years now and have a lifetime free supply. His “factory” is near my house in Canada. When I started using Légère, I used them mostly for practicing. But as Guy improved them, I have used them ore and more and have used them for recording and concerts for the last 15-16 years. Not everybody can make them work. Indeed, "if you can't play the clarinet, you can't play these reeds!" More specifically, if you can't voice correctly and do not have a properly formed embouchure, they won't work. When Guy [Légère] would go to a trade fair, amateurs would come up to his booth, try a reed, sound terrible, and then blame the reed. Guy became so frustrated that he asked Steve Cohen Steve to go with him to several conferences. If the amateurs blamed the reed, Steve would give them a quick lesson!

I do let my students try them, but I want all my students to have the experience of using wood reeds and learn to work on them. They have to learn there are no short cuts. Then they can have one in case they can't find a good wood reed. Some eventually use them all the time( like me), but they do know how to fix wood reeds.

HM: I didn't know that the Légère reeds are so sensitive to a good or bad embouchure technique.

JC: I learned that we change as much as our reeds, depending on how we feel, how nervous we might be before a concert, even how much we slept the night before. But, like wood, Leger's do change with a change in altitude. You need a softer reed in higher elevations.

HM: So, you play softer reeds - also Légère - at high altitudes?

JC: In the mountains, I take a softer reed, like wood. And when Légère reeds get warm, they become softer.

HM: I play softer reeds in summer, harder reeds in winter, and softer reeds in the mountains.

JC: That would work, yes. And what happens to Lègére: the reed has to warm up. You don't wet it; you warm it up. A reed can initially feel hard, but when it warms, it will feel softer. It can be a trap and choose a reed that works well for only part of the concert, becoming too soft as it heats up. Some players change reeds in the intermission, I often do. You have to learn how to use Legere reeds. It is not magic, and they are not all the same.

HM: And do you work on the Légère reeds, like on the wooden reeds?

JC: You can, with a scalpel. I don't; I just find another one.

Their tips are very, very thin. Thinner than wood can ever be. And they are all balanced, so if you do work on them, it is to adjust for feel.

And they do wear out. To test this, you put the reed on a flat surface and try to slide another one under it, if the reed goes underneath, it means it's bent and is near the end of its life. But this can take several months. Especially if you rotate your reeds.

HM: Longer than wood.

JC: Yes. One of the joys I have had with Legere is that when my wife comes with me on tour, instead of working on my reeds in my hotel room and worrying, we go out to dinner.

But there are many uses for them, for example, when practicing technique, the reed doesn't get tired.

If one of my students has a problem with biting, I give him a very soft reed tell them to come back with a good sound. They then have to play without biting.

HM: And not to bite…

JC: Not to bite and get a lively vibration, resonance.

HM: I played it on the contrabass clarinet.

JC: They work very well on the big instruments.

HM: People I hear playing it were a bit low on the upper register.

JC: Yes, that has to do with voicing. And it could be that they had a reed that was too soft.

A bit of philosophy

JC: I tike to tell my students: "If you can't play the clarinet well, you can't make music. If you can't make music, there is no point in playing the clarinet".

So what drives what? Of course, we all want to play the clarinet as well as we can.

And that's good, and in my mind, it's better to be an excellent musician, and it's even better to be an artist. We have been talking about a lot about the technical details of clarinet playing, tools to become a good clarinetist. An excellent clarinetist needs these tools to be a creative musician, and the musician needs more tools to become an artist. The desire to be an artist should be what drives you.

This goal is easy to forget, especially when we get busy solving technical problems. It's easy to work on technical details and forget why we are doing it. A student needs to develop their ear to the point where it leads, it gives them a reason to practice. It is the engine that drives ambition.

The wonderful saying sums it up:” if you want to play better, listen better!”

HM: So, for instance, the ability to produce a beautiful sound should be used to take the public somewhere to share your emotions.

JC: Absolutely! It is pretty simple. Have as many “tools” in your toolbox as possible and when you have problems, look in your toolbox; you might have the right tool to solve it.“

Phrasing

HM: Although this study focuses on the technical aspects of clarinet playing and teaching, I would like to touch on the phrasing chapter.

JC: What to say about phrasing? Generally, clarinet playing is sometimes considered boring by a general public which is used to hearing violinists, singers and cellists. We cannot, for example, make a slide or vibrato like a violin, it sounds ridiculous. The clarinet is not meant to do that.

The great jazz trumpet player, Winton Marsalis[1], says: “If you don't use vibrato, you have to be VERY musical.”

Since we make music by blowing air into our instrument, we need an incredibly active air column. Yet the embouchure must remain calm. I like to say: “calm face, fire in the belly”!

I use Bonade's 16 Phrasing Studies a lot for my playing as well as teaching.

EXERCISE

JC: In a Bonade phrasing study, I ask the student to do all the markings Bonade wrote, but not the notes. The result sounds like a series of long tones.

HM: So, you play an etude on one note, with all signs of dynamic, articulation and phrasing.

JC: Exactly! (Sings the beginning of the first of the thirty-two etudes, first as it is written, then only on the first note).

It becomes a long tone, and the melody is in your head. We call this the “inner line.”

That's easy, right? But when adding the notes asked, it becomes harder because of the clarinet. For example,

we must make adjustments when going over the break, and use more air in the upper register.

HM: Then the voicing becomes important.

JC: Voicing is very important and must be built into the technique.

HM: You were talking about Bonade…

JC: Yes. Bonade didn't exactly do this with me, but his demands for broad musical expression forced me to figure it out. We went through many of the Rose studies, working on voicing, articulation and finger technique. He was very nice but very strict. I was eighteen years old and had a lesson a day for about a month. It was great!

The 2 – 3 – 4 - | 1 – grouping is a well-known way of organizing both rhythm and phrasing. In my class, we called it "I - go - to – there." it is a handy technique to have mastered. I spend a lot of time working on phrasing, more than working on technique!

HM: It would be fascinating to follow up on the current project with these questions.

Thank you very much for this interview!

References

- ↑ Guy, Larry. 2018. Articulation development for clarinetists: including exercises and passages from the orchestral and chamber music repertoire, with a demonstration CD.

- ↑ Guy, Larry. 2011. Embouchure building for clarinetists: a supplemental study guide offering fundamental concepts, illustrations, and exercises for embouchure development. Stony Point, N.Y.: Rivernote Press.

- ↑ Guy, Larry. 2008. Hand & finger development for clarinetists: with exercises and illustrations from the orchestral repertoire. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press.

- ↑ Gholson, James. Interview with Robert Marcellus. The Australian Clarinet and Saxophone Magazine, Issue 2, March 1999[2]

- ↑ Stein, Keith. 1958. The art of clarinet playing. Princeton, N.J.: Summy-Birchard[3]

- ↑ Pino, David. 1998. The clarinet and clarinet playing. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications.[4]

- ↑ ¨Jeanjean, Paul. 1927. Vade-Mecum du clarinettiste six etudes speciales pour l'assouplissement rapide des doigts et de la langue. Paris: A. Leduc.

- ↑ Jean-Michel Defaye: Six Pièces d'Audition; Gary Kulesha: Political Implications; Peter Schickele: Dances for Three [5]