Finger Technique

Contributions by Interviewees

- Michel Arrignon

- Paolo Beltramini

- François Benda

- James Campbell

- Philippe Cuper

- Alain Damiens

- Eli Eban

- Steve Hartman

- Sylvie Hue 1, 2

- Gerald Kraxberger

- Seunghee Lee

- Ernesto Molinari

- John Moses 1, 2, 3

- Pascal Moraguès

- Harri Mäki, 2, 3, 4

- Heinrich Mätzener 1, 2, 3

- Robert Pickup

- Frédéric Rapin 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

- Ernst Schlader

- Thomas Piercy

- Milan Rericha 1, 2

- David Shifrin 1, 2, 3

- Richard Stoltzman

- Jérôme Verhaeghe

- Michel Westphal 1, 2, 3, 4

Basic Hand and Finger Position

In his textbook Methodische Schule der klarinettistischen Grifftechnik [Systematic Approach to Clarinet Finger Technique] on p. 16, Jost Michaels (2001)[1] mentions two principles that must underlie the study of finger technique:

„Sie sollen nicht nur die Arbeit an deren möglichst gleichmässigen und unaufwendigen Bewegungen dienen, sondern zugleich der dafür wichtigsten Voraussetzung - nämlich dazu, dass sie auch wenn sie nicht aufliegen, dennoch ihre Positionen über den für sie bestimmten Tonlöchern in einheitlich nicht zu weiten und vor allem nicht verschobenen Abständen beibehalten.“

„They [the studies that are exclusively related to the basic position of the fingers] should train not only finger movement, which should be as even and effortless as possible, but also the most important prerequisite for this - namely, that even when the fingers are not in contact, they should still maintain their positions above their respective tone holes at uniform distances that are neither too wide nor shifted.“

Historical Milestones

The clarinet’s development from a three-keyed instrument to the modern 17-keyed (or more) instruments was accompanied by changes in finger technique. These changes also influenced other aspects of basic technique, in particular, embouchure and holding. For instruments without a thumb rest on the right, "support fingers" of the right hand were used to help holding the clarinet. At the same time, the resonance and intonation of individual notes could be improved. This holding technique also allowed for a double-lipped embouchure. The embouchure itself played very little stabilizing function.

The mobility of the left thumb was – and continues to be – particularly challenging; it is the only finger to switch between four different basic positions: closed/open g1, with or without opening the overblowing flap.

Amand Vanderhagen 1785

From the instructions of Jost Michaels (2001)[1] (see above), we can see a predecessor in Amand Vanderhagen (1785)[2], who in his Methode nouvelle et raisonnée pour la clarinette [New and Reasoned Method for the Clarinet] advocates the same principles concerning finger position and movement:

„Le pouce de la main gauche doit toujours être prêt à prendre la clef, ou à boucher le trou, il ne doit en conséquence faire que des très petits mouvements: il en est de même du doigté en général; il ne faut lever les doigts qu'à très peu de distance de l'instrument, et toujours perpendiculairement. Les deux mains doivent toujours pencher vers la palle de la Clarinette. Aucun des doigts ne doivent se toucher afin de pouvoir cadencer librement; il faut que lorsqu’un doigt et levé ou même plusieurs, qu' ils restent perpendiculairement au dessus des trous qu'ils doivent reboucher, car en les retirant comme font beaucoup d'écoliers, on a toujours de la peine à retrouver les trous et cela empêche l'exécution.“

„The thumb of the left hand should always be ready to open or close the [overblow] flap. For this purpose it should make only very small movements. This applies equally to all fingerings: one should lift the fingers from the clarinet only in very small movements, at right angles above the tone holes. Both hands should tilt slightly towards the foot [bell] of the clarinet. The fingers should not touch each other so that they can trill freely and unhindered. When lifting one or more fingers, make sure that they are always perpendicular to the tone holes which they must close again. This is because when the fingers are bent back in the raised position, which can be observed in many students, it is always difficult to precisely cover the tone holes. This makes playing more difficult."“

Iwan Müller 1812

The "clarinette omnitonique" [omnitonic clarinet], by Iwan Müller (1812) made legato connections between all tonal steps possible, but assigned new tasks to the thumb of the right hand and the little finger of the left hand, through a new thumb key and a key on the back of the instrument, respectively. This limited the extent to which the thumb could be used as a "holding finger" and to which the little finger on the right hand could be used as a supporting finger, resulting in considerable changes in holding the instrument, which also affected the Embouchure technique. This may be one reason why this system did not meet with the hoped-for acceptance when it was brought before a commission of conservatoire professors in Paris around 1820. In particular, the new key for the right thumb brought with it new distribution of the instrument’s weight on the hands and changed the holding technique. In order to find sufficient stability, a mandibular embouchure without double-lipping proved to be more practical. In Paris, however, the double-lip approach was still used (until about 1920/30).

Around 1860, the further development of the Iwan Müller clarinet by way of the Baermann-Ottensteiner clarinet (see Oskar Kroll (1965) [3] led to the Oehler system which is widely used in Germany today.

Hyacinthe Klosé and Alfons Buffet 1839

The flutist Thobald Boehm developed ring keys (1832), which made it possible to close two tone holes with one finger movement and thus to play a diatonic scale without a fork grip. Hyacinthe Klosé and Alfons Buffet transferred these developments to the clarinet (see Ridley, 1986)[3]. At the same time, the hard to operate keys on the back of the instrument (for the legato connections between the long notes e/b and f sharp/d sharp) were replaced by additional keys for the right and left little fingers, which also allowed for more virtuosic mobility. On today's Oehler system, which resulted from further developments of the Iwan Müller and Baermann-Ottenstiener clarinet, all fingers of both hands must "know" different positions for operating different keys. The Boehm system spares the index and middle finger of the right hand from having only two positions (open or closed).

Summaries from the Interviews

Finger technique is considered one of the central instrumental skills. It is about control and coordination of finger and hand movements. Finger technique enables the precise shaping of rhythmic figures and regularity in the musical flow. It not only enables virtuosic instrumental playing, but is also discussed as a decisive factor for the quality of legato playing in slow passages. Whereas musical objectives are easier to formulate and control, the description of correct – and thus efficient – posture and movement patterns poses greater challenges for teachers and learners.

Technique and Interpretation

When his students struggle with fast, technically difficult passages, Michel Arrignon asks the question "could you sing this part?" Giving the technically difficult passages a musical meaning, i.e. being aware of the musical phrasing and rhythmic accentuation, is a great learning aid. Even the basic technique exercises, scales, chords, and etudes should always appear in a musical manner.

Alain Damiens has students sing the basic tone or other intervals simultaneously with the scales or etudes. Thus there is no danger of working on the technique unmusically, "comme un cheval" [bullishly].

Philippe Cuper remembers the lessons with Guy Dangain, who prepared him for the entrance examination to the conservatoire: he had to spend up to two hours every day for about a year studying scales and chords. Philippe still recommends this to any student who aspires to a professional career.

Alain Damiens invents his own etudes based on literature currently being worked on. For Michel Westphal, the final touch of technique takes place in relation to the literature played.

Frédéric Rapin has students take personal responsibility for practicing the technical exercises, scales, and chord studies independently at home. Only in the case of obvious deficits does he incorporate technical exercises into each lesson. Like Paolo Beltramini, he combines passages from the literature currently being played with the underlying and scale and chordal structures and repeats them across the entire range.

Lessons for Beginners

Sylvie Hue emphasizes that a child wants to play melodies as quickly as possible. The lessons should be based on this. Playing music for wind instruments is vital, as it encourages use of the reed and rhythmic music making (see also Alain Damiens). This will in turn motivate the children to study scales and chords, because they will be able to make big advances and gain an enormous amount of time. This is also how she conceived her teaching work L'Apprenti clarinettiste [The Apprentice Clarinetist] (2001)[4].

Seunghee Lee compares scale and chord studies and etudes with learning the alphabet: in order to be able to read fluently, each child begins by learning the letters, then syllables, words, and finally whole sentences. Only professionals can start learning a piece straight away and only thereafter convert individual passages into etudes.

Sound Production before Finger Technique

François Benda, James Campbell, Milan Rericha, Richard Stoltzman and Michel Westphal identify a solid embouchure and well-founded airflow as prerequisites for good finger technique. No matter how brilliant a finger technique is, it cannot be musically satisfactory on its own. Sound, articulation, and phrasing must be consciously prepared and designed.

Frédéric Rapin also ascribes great importance to the study of scales and chords, but always combines work on finger technique and fluency with tone formation. He proceeds in small steps and initially allows the scales to be played only in the range of an octave, with the focus on balanced sound and dynamics, as if it were a concert performance. Only then do variations with different rhythms, articulations, and tempi follow.

Slightly Bent or Stretched Fingers?

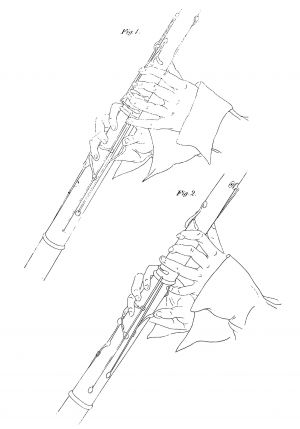

In order to have a natural hand shape when playing, François Benda, Harri Mäki and Ernesto Molinari suggest the following procedure: when the right hand is dropped loosely next to the body, the hand is relaxed, the fingers are slightly bent. The clarinet can now be placed horizontally in the right hand by the left hand, thus adopting the natural hand and finger positions for clarinet playing. The ideal hand shape can be found by loosely embracing the opposite wrist (Ernesto Molinari).

Sylvie Hue attaches great importance to the fingers resting on the clarinet in a slightly rounded shape. For beginners, special care must be taken to ensure that the right index finger does not support the weight of the clarinet on the E-flat key. The combination of mouthpiece and reed should be as light as possible and should not require unnecessary strength that can then cause tension in the whole body.

Heinrich Mätzener makes sure to find physically correct postures of hand and finger from the very beginning, because if bad postures become habit, these must be laboriously relearnt. He also refers to Ulrich Dannemann’s Isometrische Übungen für Geiger [Isometric Exercises for Violinists] (1982)[5] and recommends strength training for the hand if necessary. The movements should always be performed with fingers slightly bent from the base of the finger joint.

Milan Rericha also holds slightly bent fingers as an ideal starting position, but would not insist on changing this in a student who has good fluency with stretched fingers. For Milan, it is important that the fingers move playfully, as on a piano keyboard; This also leads to better bearing of the clarinet’s weight.

Michel Westphalclobserves not only the joint positions of the hand, but also those of the shoulders and arms, which allow for optimal hand placement. Depending on the size of the arms and hands, the constellations are to be chosen differently. He notes that the instruction to play with slightly bent fingers can lead to tension and poorer results, especially for beginners.

Individual Differences

Different hand and finger dimensions result in different definitions of an optimal hand position. [François Benda#Individuelle Unterschiede|François Benda]]: It also makes sense to adjust the instrument depending on the size of the hand. For example, in the case of a very large hand, a pad under the thumb rest has the effect of a larger diameter of the clarinet; if the fingers are particularly short, it is worth having the instrument maker extend the levers for the little fingers.

Flexibility of Wrist and Forearm

François Benda and Heinrich Mätzener maintain that both index fingers need a flexible hand position to operate additional keys - on the right the e flat/b2, on the left the a and g sharp keys. It would not be economical to only operate these keys with finger movements. To get to know these hand positions, all tone holes can remain closed while the hand alternately assumes all the different positions needed to operate the individual keys. Trills with the left or right 4th finger can also be performed using a rotation of the forearm. Played slowly, this movement is similar to drinking from a glass; as a trill it is similar to playing tremolo octaves on a piano. The other fingers remain in place, and even with a small rotation on the fingertips, the tone holes remain closed.

Execution of Finger Movements

Depending on the type of finger movement – strong, large, and fast, or small, precise, and smooth – the musical expression changes. For playing legato, finger movements are suitable, comparable to a sneaking cat. For a brilliant, virtuosic performance, the movements can also be a bit more athletic, but always small and precise.

François Benda works with fast finger movements, which are slowed down shortly before the tone holes are closed.

As a legato exercise, Alain Billard has his students perform a glissando with their fingers; the tone holes are opened and closed so slowly that micro-intervals are created. This exercise also trains the flexibility of the air flow.

Eli Eban refers to Robert Marcellus and chooses the type of finger movements according to the character of the music. In an Adagio the movements can be somewhat larger and slower; in fast passages the fingers jump from tone to tone in small, rhythmically precise movements (see also Daniel Bonade, (1962)[6].

John Moses refers directly to Daniel Bonade: in legato playing, he reaches out with his fingers first in the opposite direction and then slowly brings them to the clarinet. He compares the closing of the tone holes with the squeezing of a tennis ball, as opposed to a finger movement that would be comparable to percussive typing.

Harri Mäki also carries out this principle of "legato fingers" in slow passages in the opposite direction: when lifting a finger, he first presses it into the instrument with light force.

David Shifrin relativizes the meaning of the "legato finger technique", the lifting of the fingers before they slowly close the tone hole. A smooth legato is not just a question of finger technique; it is more important to consciously use the air flow and vocalization "between the notes" and not to react to the changes when a new pitch is reached. He achieves the best results with a (not too) small and powerful, very definite movement, comparable to the fingering on a cello fingerboard. However, the fingers must never strike the clarinet, but should be pressed a little into position as if they were squeezing a tennis ball. The fingers are in a slightly rounded position.

Pascal Moraguès, like Milan Rericha, also recommends the smallest possible finger movements for the legato.

For Robert Pickup it is very important to always play with the smallest possible finger movements. The fingers are always exactly above the tone holes when open. There are basically two finger movements: the "legato fingers" and the "articulating fingers." The difference in movement is that when playing legato with slightly bent fingers, the movement takes place in the base joint of the fingers. With the "articulating fingers" the focus of attention is on the fingertips. This stabilizes the bent finger shape a little more clearly and the fingertips hit the instrument in an “articulated” manner.

Thomas Piercy retrained his technique when he was over forty years old: he transformed large, sometimes uncontrolled movements into the smallest possible precise movements exactly above the keys and tone holes. When practicing, the little fingers had to remain on the F and E keys when they were not in use (see also Flexibility of Wrist and Forearm. This change was very time-consuming, but he found it was definitely worth it: not only his finger technique, but also his entire playing developed to a higher level.

Depending on the style Michel Westphal uses the possibilities of striking the clarinet with the fingers noisily or moving them very smoothly and smoothly.

Frédéric Rapin compares finger movements to the fine movements used to articulate with the tip of the tongue, and places the peripheral focus of the finger movements on the foremost finger joint. Of course, it is not possible to play exclusively with these joints. However, if the focus of attention is placed here, the fingers gain a certain stability, the finger movements become more precise, and the acoustic result becomes clearer. Special attention is paid to the closing of the tone holes; lifting the fingers is easier and does not require special practice. This technique also produces good results when playing legato. For the development of a virtuoso finger technique Frédéric recommends practicing trills.

Robert Pickup, who can imitate different reed articulations with the finger movement, follows a similar approach: in technically brilliant passages the focus is on the fingertips, in legato passages the fingers are more relaxed and the movements are controlled from the finger base joint.

≠≠Thumb Rest, Position, and Strength of the Right Thumb≠≠

See also Holding the Clarinet

Many of the interviewees, such as Alain Damiens, Sylvie Hue, John Moses, David Shifrin, Jérôme Verhaeghe, choose a thumb rest position that is as high as possible, so that the right hand index finger and thumb are roughly opposite each other. Since most clarinets today have a movable thumb rest, the position can be adjusted to fit individual needs. It is also worthwhile, if necessary, to have new holes drilled further up for an optimal thumb rest position. If pain is felt in the right thumb, pause immediately and check the shape and position of the hand and thumb.

Alain Damiens compares the position of the right thumb with holding a pencil: the fingertips of the index finger and thumb are opposite each other. With a thumb stretched down, the remaining fingers of the hand involuntarily stretch and tense up. All interviewees recommend checking this. If the thumb rest is too low, it can be more difficult to operate the side keys with the index finger (David Shifrin). The aim should be to be able to perform all fingerings, including those with the right-hand side keys, with the smallest possible movements.

François Benda and Pascal Moraguès point out that the weight distribution of the instrument changes depending on the position of the thumb rest. The ideal position is where the thumb rest allows the clarinet to be balanced on the thumb. If it is too high, the instrument can exert too much pressure against the upper teeth.

Sylvie Hue: the thumb should be approximately at the height of the index finger, and a nice curvature should be formed not only by the fingers, but also by the inside of the hand. Like Sylvie Hue, Michel Westphal recommends strength training for the right thumb, in which fingers 2-5 remain loose. Hue would also very much welcome instrument makers developing means of reducing the clarinet’s weight (lighter keys; thinner outer walls), as well as a thumb rest that could stabilize the hand in a natural shape.

Gerald Kraxberger adds that the thumb rest should not be set too low, so that the first thumb joint bears the weight in the correct position. During strength training, agonist and antagonist should always be given equal attention. Particularly with trills, the opening – the movement away from the instrument – is just as important as the closing of the tone holes and keys. Ernst Schlader emphasizes the necessity of movement, sport, and strength training for the whole body. These are important prerequisites for technical ease on the instrument and balances out hours of practicing and working on the computer.

James Campbell, Eli Eban and Heinrich Mätzener are careful to hold the thumb in a slightly concave shape. Thus, the remaining fingers also take on a slightly rounded shape. A thumb stretched downwards would automatically result in the fingers being stretched and lying close together and put the hand under an undesirable amount of tension. If the thumb, bent slightly inwards, forms a not-quite-closed oval with the index finger, it brings the whole hand into a good position. When holding the clarinet, a good cushion under the thumb rest is very important.

During the strengthening exercises by Greg Mesplié (see picture on the left and video), one must be careful not to push through any joints. The point is to stabilize the joints with the muscles; this strength is the basis for a relaxed fluency. The strengthening exercises for pianists by Erwan are also recommended.

Frédéric Rapin and François Benda first put all their fingers on the clarinet. Then the thumb can find its most comfortable position. Rapin personally chooses quite a high position for the thumb rest, but does not want to make this a general rule, but rather to take into account the individual differences in hand size and shape.

Michel Westphal would not exaggerate the importance of the thumb rest position since it is placed differently depending on individual requirements. Changing between different instruments (basset horn, basset clarinets with thumb keys, historical clarinets) requires a higher position of the thumb rest in order to be able to operate the thumb keys.

Working on Technically Difficult Areas

Following the basic principle of slow to fast, David Shifrin breaks down difficult passages into smaller groups of notes and practices them in different tempos and rhythms. Our brain cannot reproduce longer, faster passages note for note. Such passages must be broken down into successive sequences of shorter groups of notes and then the whole passage can be played as a sequence of smaller groups of notes. Patterns of longer and shorter note values are often repeated until the movement sequences can be played back reflexively and strung together.

John Moses recommends working through difficult passages in different tempos and rhythms, as well as in different transpositions, so that upon returning to the original version, it seems easier.

Frédéric Rapin insists that before working on the speed in technically difficult passages, the passage should be executed with an optimal sound quality.

Harri Mäki "copies" the fluency of the most agile finger: the movement of a slower finger is contrasted with the fast one until both can achieve the same speed.

Milan Rericha works out an even fluency using all possible trills. Special attention is paid to the trill g-a/d-e (right hand). See also François Benda.

Becoming Fluent

Checklist

When practicing finger technique, the following is recommended:

- The fingers should always remain on or directly above the keys / tone holes

- The fingers should always make the smallest possible movements

- Hard striking of the fingers on the instrument results in accentuated tone changes

- All joints should be slightly bent – do not allow fingers to be stretched through!

- The thumb of the right hand should be bent slightly, if possible

One of the most important general learning rules of acquiring professional-level technical playing skills is the number of practice hours that a prospective professional musician has logged by the age of 20. This is confirmed by a study by Malcom Gladwell[7]: 10,000 hours by the age of 20 are considered a prerequisite for a top career as a musician. Anyone who has only spent 4000 hours practicing must forgo a high-flying career. Of course, it is not only the quantity but also the quality of practicing – which includes a body-compatible finger technique – that plays an important role.

Literature

- Christoph Wagner, Ulrike Wohlwender: Hand und Instrument. Musikphysiologische Grundlagen. Praktische Konsequenzen. Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden 2005

References

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 Michaels, Jost, and Allan Ware. 2001. Methodische Schule der klarinettistischen Grifftechnik Ausgabe für Böhm-System = Systematic approach to clarinet finger technique : edition for Boehm clarinet. Frankfurt am Main: Zimmermann.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 Amand Vanderhagen: Méthode Nouvelle et Raisonnée pour la clarinette. Boyer, Paris, 1785

- ↑ Ridley, E. A. K. "Birth of the 'Boehm' Clarinet." The Galpin Society Journal 39 (1986): 68-76. Accessed August 20, 2020. doi:10.2307/842134.

- ↑ Hue, Sylvie (2001). L'Apprenti clarinettiste, Manuel pratique pour débutant. Vol.1&2. Combre, Paris

- ↑ Ulrich Dannemann: Isometrische Übungen für Geiger. Braun, Duisburg 1982

- ↑ Bonade, Daniel. 1962. The clarinetist's compendium: including method of staccato and art of adjusting reeds. Kenosha, Wis: Leblanc Publications. S.2 [1] {04.27.2001}

- ↑ Malcom Gladwell: Outliers: The Story of Success. Little, Brown and Co., New York 2009. [2]{04.27.2001}